Raiding their Mom, Dad, Aunts and Uncle's closets is one of the ways Kwamena Boison and Yayra Agbofah unknowingly began their case study about fashion. A sort of treasure hunt that led to enlightenments about the world of clothes: “These were clothes from the sixties or seventies, and we realised how much passion people had for quality garments back in the day, compared to today.” By today, he is referring to fast-paced garment manufacturing and consumption that has led to the production of poor-quality fast fashion flooding industry and consumer closets alike.

On reviving fashion through textile waste upcycling

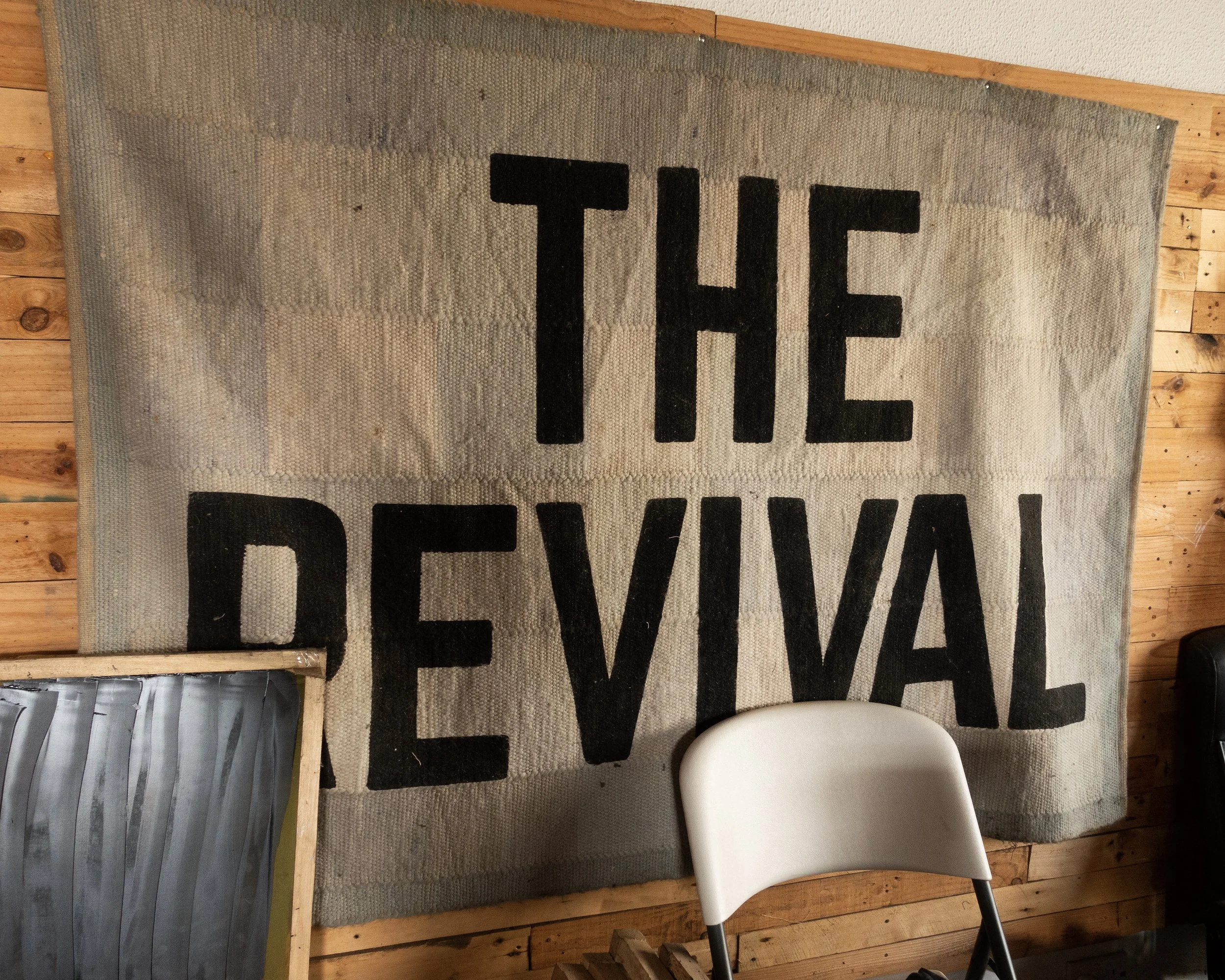

with Kwamena Boison from The Revival

“ Deep down, I envision us deleting the word sustainability from what fashion is.” Kwamena Boison

Kwamena and Yayra founded The Revival, an Accra-based, community-led non-profit. Their goal is to educate and raise awareness on the impact of fast fashion while creating jobs through championing upcycling with textile waste coming into Ghana from the Global North. If you have been in the sustainable fashion space for a while, you would have heard of Waste Colonialism. If not, here is a quick breakdown. Waste colonialism is when a group of people uses waste and pollution to dominate another group of people in their homeland. In the case of Accra, Ghana, the city receives up to 15 million discarded secondhand garments weekly from Global North countries. The UK is a leading importer of such garments into the country. It is crucial to highlight the latter because this ties into a colonial history. Ghana was a British colony for almost a century and during that time Britain oppressed and stole from the nation. Although, Ghana gained independence in 1957 (the first sub-Saharan country to do so), colonisation since then has morphed into an unjust economic power play. The dumping of discarded fast fashion garments into the country is an ongoing testament to this. The term Waste Colonialism was coined in 1989 when African countries expressed concern over the dumping of hazardous waste from high-GDP countries to low-GDP countries, a power play stemming from that very colonial past.*

“Those things are at the highest risk of going into landfill, into our water bodies, so for us, it is like a rescue mission.” Kwamena on Global North waste entering Accra.

Despite the complexity of this dynamic, many non-profits, initiatives and organisations just like The Revival have sprung up within Global South nations to tackle the issue. From Remade Cambodia in Cambodia to Africa Collect Textiles in Kenya or even Ecocitex in Chile, these initiatives are managing the end of the lifecycle of the billions of garments created by Western fast fashion brands.

However, for Kwamena The Revival was not created necessarily in response to this issue, although it later became a space of solution for it. It was first a childhood passion for creativity and the buzzing inspiration of Kantamanto Market that brought it to life: “There was a time when I bought shorts a lot. I would find myself cutting them up, using extra scraps to create pockets. That was before I met Yayra in 2015. We started talking about all things fashion and creativity, and that’s when The Revival started coming to life.” He adds that Kantamanto to him growing up was like a fashion Disneyland: “ To me, it is a fun space. I went there excited to see all the chaos but it was also organised chaos. It sparked something inside of me to see people who were already upcycling in a way that was so organic because it was being done without the label of sustainability as we know it now.”

Today, upcyclers in Kantamanto are an integral part of the work done at The Revival. Go to their studio any day and you will most likely see a local upcycler hunched over a new creative design. Making something new out of an old garment. The studio itself is a treasure chest. Much like Disney, trinkets and old materials seem to transform into something new as if by magical hands. Imagine a winter puffer jacket reimagined as a versatile hooded backpack or distressed denim now framed as art on a wall. They organise pop-ups across the city that often attract students, diasporans and some locals. In Accra, the educational piece about the impact of fast fashion is not always straightforward, but Kwamina is well-versed in the cultural discourse: “ If I go to Kantamanto, I won’t use the word sustainability because it just doesn’t resonate there. I know that people like me like to listen to things in a certain language, so I don’t fuss about political correctness. We need to respect the culture.” He understands it’s still crucial to speak the global economic language by using these words to export and share the local innovations he witnesses every day. A key project that the studio focuses on is the production of upcycled denim jumpsuits for pineapple farmers. Pineapple picking means getting bruises and cuts from the sharp fruit. Kwamina explains that local pineapple farmers go to the market to buy cheap clothes they layer on to pick pineapples. These denim jumpsuits help farmers avoid getting hurt while working and are durable which means farmers don’t have to keep buying cheap secondhand clothes to wear for work. There is a sort of return to fashion and upcycling as practicality and functionality. So many of these notions are lost to fast fashion brands who chase profit rather than quality and long-term wearability. What if fashion went back to functionality with style? This project proves that it is possible and feasible with clothes that already exist.

“To me, Kantamanto is a fun space, I go there excited to see all the chaos but it was also organised chaos. It sparked something inside of me to see people who were already upcycling in a way that was so organic because it was being done without the label of sustainability as we know it now.” Kwamena highlights.

The Revival collects third-grade garments from Kantamanto. These are the poorest quality or untrendy items found in imported secondhand bales.“ Those items are at the highest risk of going into landfill, into our water bodies, so for us, it is like a rescue mission.” They also organise pop-ups where upcyclers create partially made items tailored on the spot for whoever chooses to buy that garment. It’s a wonderful way to highlight Ghana’s already entrenched culture of personalising clothes and tailoring to fit a unique body. True Ghanaian fashion is rarely one size fits all. The pop-ups usually start with panels and talks aiming to immerse the public in the fast fashion issue and the solutions embedded in the culture. Although the traditional textile industry of Accra has somewhat suffered from the import of secondhand clothing, Kwamina believes in looking ahead: “ I like to see this as an opportunity. Ghanaian creativity does not end at traditional wear. In fact, these are often only worn on special occasions. Culture evolves, and we must decide to serve humanity with our culture as we always have. Despite the challenges in Katamanto, it never removed our humanity. Our creativity thrives. This is all a chance to imagine what Kente could become with the resources we have today.” There is a sense of looking to the past while propelling fashion into the future. It's about seeing opportunity in organised chaos and reviving the old to benefit the future.

“ Culture evolves, and we must decide to serve humanity with our culture as we always have. Despite the challenges in Katamanto, it never removed our humanity. Our creativity thrives.” Kwamena Boison

“Deep down, I envision us deleting the word sustainability from what fashion is. It is not even real. It is an idea we’re trying to achieve. It’s a goal but it’s not real yet. Plus, it is now such a buzzword.” If sustainability in fashion is something practised across cultures in a not-so-distant past, that means it was what fashion simply existed as. In the current landscape of new definitions, the word has somewhat lost its way and in multiple cases become a scapegoat for brands looking to do nothing but drive profit. Perhaps Kwamina is right. Erasing the word could force us to hit the reset button on fashion. Maybe it would allow us to make fashion what it was always meant to be and has been in the past.

“ I like to see this as an opportunity. Ghanaian creativity does not end at traditional wear. ” he adds