The countdown for textile waste accountability has begun…

Join the Speak Volumes campaign, one of the ways we can all support the rise of Western brands being held accountable for textile waste through policy, campaigning, plus individual and collective action.

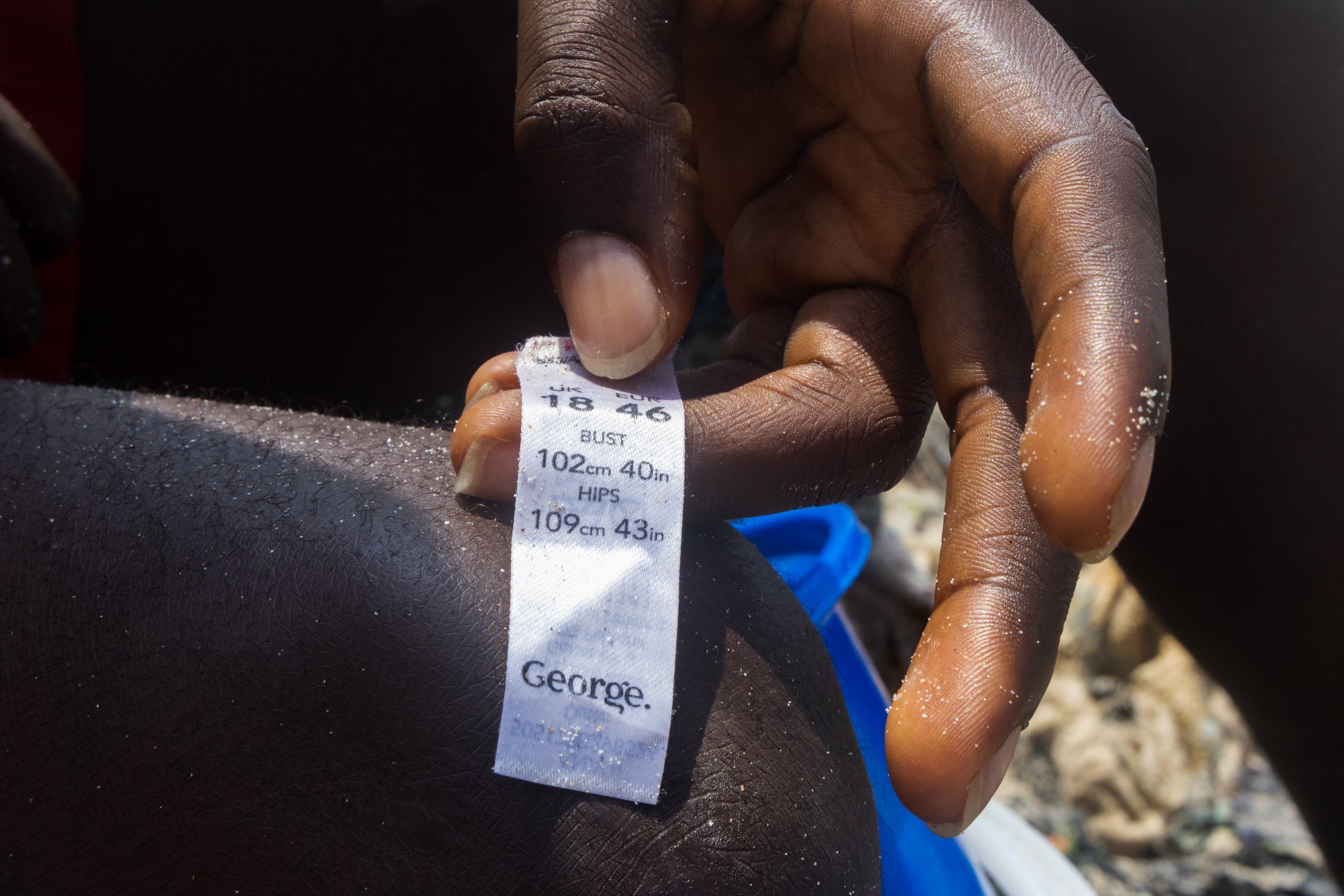

“Obroni wawu”. This is a term frequently heard as you bustle through the thriving second-hand clothing market in Kantamanto, Accra, Ghana. The term translates to “dead white man’s clothes”, a local term used to describe the second-hand clothing that is imported into the market weekly from Europe and the US. Except these are not the clothes of dead people. The large inflows of second-hand clothing swarming the market is a symptom of fashion overconsumption in these exporting countries, where most fashion is disposed of within a year of purchase. Ghana-based non-profit, The OR Foundation, working at the intersection of environmental justice and fashion development for the Kantamanto community, estimates the incoming clothing volumes to be as much as 15 million tonnes of garments per week, which has already exceeded the local landfill’s capacity to process incoming textiles, consequently flowing into waste streams and polluting local beaches.

Now the second-hand textile trade is not new to Ghana, or other countries across the continent. This trade has been an integral part of the local community, dating back to the 1960s, when upcyclers and retailers repair, and even reinvent secondhand clothing ready for sale and reuse. Arguably, the market’s existence represents the foundations for a circular fashion model where products are kept in use avoiding landfills, while generating local income.

A key disruptor to the economic prosperity and environmental sustainability of this model has been the rise of the fast fashion industry. With its high production volumes, produced and sold at lower costs, this has brought with it lower quality clothing that consumers may only get a few uses out of. Over time, we have seen a decline in the use of clothing where it is estimated that more than half of fast fashion purchases are disposed of within a year, partly due to this poor quality. This lower-quality clothing makes its way into markets like Kantamanto, where sellers purchasing bales of clothing find most items cannot be upcycled or sold. Conducting primary research on the ground, The OR have found on average, 40% of clothing within a bale leaves the Kanatamanto market as waste, to then be discarded on beaches and overflowing landfills, to no economic profitability.

As stakeholder pressure mounts, fashion brands, like H&M, have introduced take-back schemes, marketed as circular initiatives to curb textile waste, by allowing consumers to donate clothing that can be directed towards reuse markets or recycling. However, these schemes have faced much scrutiny reflected in that:

- Consumers can donate clothing in exchange for discounts, reinforcing rather than curbing clothing consumption.

- Collected garments rarely end up recycled, revealed by The Changing Markets Foundation’s year-long investigation tracking garments dropped off at an H&M store in Mali, where one garment remains unsold in the market, the other in a wasteland.

The research exposes such strategies to greenwashing accusations – environmental claims considered to be misleading about the true environmental impacts. Indeed, the fashion industry has come under increasing scrutiny over allegations related to “recycled materials” clothing labels when it is not clear what the source material is, or whether the garment can be adequately recycled post-use. Other examples of greenwashing to be weary of include reliance on recycled polyester which predominantly comes from plastic bottles; reliance on sustainable certifications which cannot effectively verify product sustainability; and introductions of sustainable or eco-ranges which make up only a small proportion of a brand’s product portfolio.

However, the regulation to address greenwashing claims is evolving, as the UK has implemented the Green Claims Code to penalise brands for greenwashing, a regulation also proposed by the European Union (EU).

Further, this also highlights the ineffectiveness of brand strategies to address downstream impacts of textile waste in the Global South, and African governments are responding. In September 2023, the Ugandan president declared “war on second-hand clothing”, proposing a ban on clothing imports. He follows the footsteps of countries like Rwanda and Indonesia which have implemented similar prohibitions, in the hopes of reviving the local textile economy. However, this hard stance was not favoured by all, including the local Ugandan retailers. As we have discussed, the second-hand clothing trade cannot be overlooked as an important source of income for locals, spurring local creativity within the textile industry. At S&S, we believe such strategies only serve to push the problem onto other geographies, heightening the textile inflows and limiting waste management resources for countries like Ghana, whilst cutting off a source of vital income for Uganda’s retailers and up-cyclers.

Spurring on sustainability across the fashion value chain will require all actors to make sustainable decisions. And this starts with the decision-makers at the top of the chain, including regulators who define the rules of the game by which all fashion brands must play. This is where we want to highlight the role of the incoming EU 2030 Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles that will put greater accountability on brands to tackle waste.

The Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) lies at the heart of this strategy, where fashion brands and retailers will cover the costs for textile collection, sorting, reuse, and recycling. Costs are to be paid through an EPR fee, determined by the environmental performance of textiles, where harder-to-recycle materials will be subject to higher fees, a principle known as ‘eco-modulation’. This regulation will also coincide with the 2025 EU regulation requiring Member States to implement a separate collection of textiles.

The success of the EPR will be determined by whether:

- The EPR fee can incentivise brands to enhance product reuse and reduce waste.

- Funds are distributed to stakeholders in recycling and most impacted by textile waste.

Brands could consider getting ahead of regulations by designing clothing to last longer and adopting environmentally preferred materials that are easier to recycle therefore facing lower EPR fees. Further, current take-back schemes could be revised to ensure waste management partners adequately resell or recycle garments, eliminate discounts, and publicly disclose the scheme’s performance.

-

OVER TO YOU

- OVER TO YOU

—> STOP WASTE COLONIALISM

EPR programs must align with the reality of how waste flows around the world, to ensure funds are accessible to affected stakeholders in the Global South, including accounting for the current loss and damage already incurred. This is why Ghana-based non-profit, The OR Foundation is calling for the EU’s incoming Extended Producer Responsibility regulation to include:

A fair EPR fee, starting from $0.50 per new garment and following an eco-modulated fee structure, where the brands that produce the most, pay the most.

Global accountability to ensure the funds are transferred to vulnerable communities bearing the brunt of textile waste generated by the Global North.

A requirement for brands to disclose their production volumes, which could then inform targets to reduce clothing production, by at least 40% over the next 5 years.

To learn more and stand in solidarity with The OR Foundation, you can sign onto the campaign using the link here: https://stopwastecolonialism.org/

—> SPEAK VOLUMES

What does overproduction in a fashion brand look like? The reality is, we do not know as brands are currently not mandated to report these figures.

However, there is always an opportunity to change this, The OR Foundation, is also leading the charge in calling on fashion brands to voluntarily report their 2022 production volumes as a first step to tackling textile waste. Through the #Speak Volumes Campaign, you can support The Or Foundation’s mission to hold brands accountable.

Using the link, you can nominate three brands you wish to see #SpeakVolumes. The OR Foundation will then contact the brands on your behalf, in a public call to action. Already, brands such as ASKET, Collina Strada and Lucy & Yak have accepted the call and made their production volumes public.

https://stopwastecolonialism.org/speak-volumes/

—> JOIN & SUPPORT ANTI-FAST FASHION INITIATIVES

Fashion Revolution happens every 24th of April, join to ask brands #whomademyclothes and hold them accountable in any other way

Remake is a fantastic global community of changemakers, follow or join your local ambassadors to create change wherever you are

Black Girl Environmentalist is a movement centering intersectional climate justice and action through the voices of people of colour. It’s a great space to connect and be inspired to act beyond justice in the fashion industry.

Fashion Revolution: https://www.fashionrevolution.org/

Remake: https://remake.world/

The OR Foundation: https://theor.org/